UZI Conversions - Page 2

|

UZI Conversions - Page 2 |

What’s so Different About a Semi-Auto Carbine?

Like other semi-auto derivatives of ex-military pattern machine guns, the UZI semi-auto carbine had to undergo a significant redesign from the SMG parent in order to pass the BATF’s measuring stick to allow importation and sale to U.S. citizens as a Title I firearm. Obviously, such changes are made with the intention of NOT allowing an easy conversion into a machine gun, and it is important to fully understand these engineering changes. A proper, safe, and legal conversion will have retained the inherent safety features of the parent SMG design, while rendering as close as mechanically possible a virtual copy of the SMG functionality and aesthetically. Israel Military Industries (IMI), unfortunately for the NFA collector community, went far beyond the absolute minimum changes required from the SMG design to allow importation and sale in this country. These extra semi-auto only features are the central focus of most of the complaints leveled at conversions of these guns, with regard to function and user-friendliness.

The

differences between a functional conversion (one that merely duplicates

functionality, full-auto only, or selective fire) and a complete conversion (one

that virtually replicates the original SMG in all aspects including function,

parts interchangeability, and appearance), are significant. They can cause

extreme variations in the fair price range of differing guns. To gain a complete

understanding of the selection and desirability of available guns out there,

let’s first take a look at the basic mechanical differences between the SMG and

the semi-auto carbine (as originally imported.)

The

differences between a functional conversion (one that merely duplicates

functionality, full-auto only, or selective fire) and a complete conversion (one

that virtually replicates the original SMG in all aspects including function,

parts interchangeability, and appearance), are significant. They can cause

extreme variations in the fair price range of differing guns. To gain a complete

understanding of the selection and desirability of available guns out there,

let’s first take a look at the basic mechanical differences between the SMG and

the semi-auto carbine (as originally imported.)

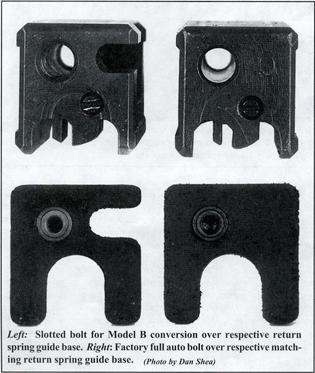

The single most important difference between the original SMG and the semi-auto carbine is in the respective methods of operation. The SMG fires from the open-bolt position using a fixed firing pin. The carbine had to be redesigned to fire from the closed-bolt position, utilizing a striker. This was solely to pass importation restrictions based upon a pending ruling prohibiting the manufacture of semi-auto Title I guns that fired from an open bolt. To this end there were several significant design changes made. The first was the installation on the rear upper right side of the sheet metal receiver of a long piece of rectangular shaped metal bar (known as a “blocking rail”) that prevented the drop-in installation of the SMG type, fixed firing pin, open bolt. In order to accommodate the blocking rail inside the receiver the semi-auto bolt has a full-length notch cut in its upper right side to allow passage over the blocking rail. Since the gun could not use a fixed firing pin a striker mechanism was incorporated into the bolt group, which now comprised a slightly shorter bolt with a full length hole drilled through its center to accommodate a moving firing pin, this pin came forward upon, sear release, to strike the cartridge primer. The bolt itself merely reciprocated within the length of the receiver housing, with each shot closing upon the freshly chambered round. The striker assembly stayed caught by the sear in the same rear position of the former SMG open bolt. The striker assembly itself comprised the long firing pin and square section of steel that has a sear holding notch cut into its bottom surface, along with a separate spring to provide the striking energy. The semi-auto now had two separate spring assemblies; the main recoil spring (attached in the familiar place on the bolt itself), and the smaller striker spring. There is an interconnecting slot cut into the left side bottom of the semi-auto bolt to mate with the long arm of the striker assembly. This assures proper alignment during movement. Due to the fact that the striker arm (contained the single sear notch) the right bottom ridge of the semi-auto bolt that would normally contain a sear notch in the SMG bolt is milled open from the rear of the ejection opening, to slightly ahead of it. The SMG bolt is solid on top and side faces, except for the sear holding notch, and the ejection port opening. To finish out the bolt group changes, The SMG has a different type of extractor than the semi-auto bolt. The lip of the semi-auto extractor is considerably thinner and shallower than that installed on the SMG bolt, for unknown reasons. It is clearly desirable to have the SMG version installed in a full-auto gun, and probably any version of the gun. They are completely interchangeable. Lastly, a note is in order on the two different kinds of semi-auto bolts on Model A guns, as this has an important bearing on how these guns may have been converted to the full-auto fire mode. When IMI first designed the Model A semi-auto bolt the bolt face was identical to the SMG open-bolt design (save for the deletion of the fixed firing pin) in that it incorporated a full-circumference cartridge holding rim. This cartridge holding rim was designed to snap around the base rim of the cartridge and hold it in position as it entered the chamber, just prior to contact with the fixed firing pin. Later Model A, and all Model B, guns have the lower section of this rim machined off, as another disabling design feature, to preclude easy modification to full-auto fire, as will now be discussed below.

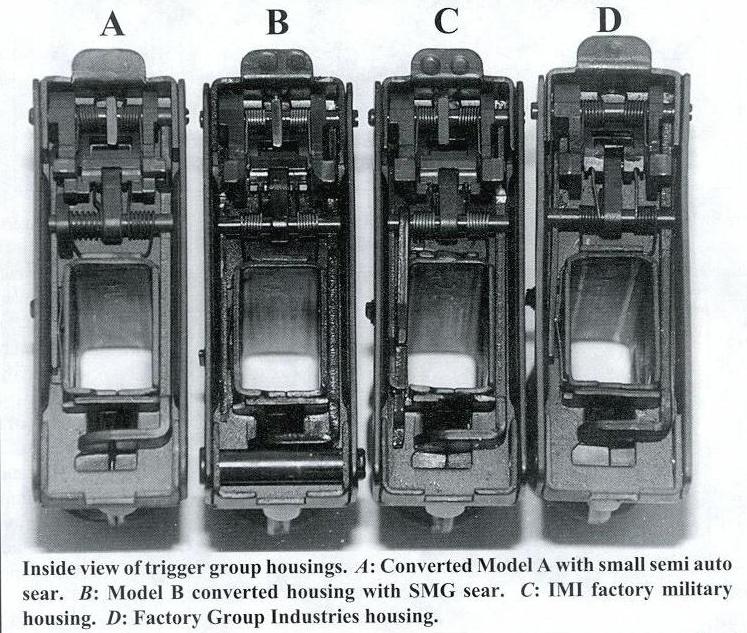

Now,

with the mode of fire changed, the fire controls had to be similarly altered.

All fire-control parts are contained in a separate housing attached centrally

below the receiver of the gun, and which also comprises the pistol grip and the

magazine well. The SMG fire-control assembly allows for three control positions,

safe, semi-auto, and full-auto. The selector levers have a small right angle,

finger-like, bent piece of metal which, in a SMG installation, moves forward and

bypasses the disconnector function in the fully forward full-auto position. For

semi-auto fire to occur it is placed in the middle position, where it can

function the disconnector, releasing the sear after the trigger nose drops. To

force the condition of semi-auto operation, whereby the disconnector is

activated continuously, it would be required to mechanically preclude the

selector from moving forward past this point. The alterations were made to the

semi-auto grip housing by adding a small block of metal inside the front center

shelf of this housing to preclude the selector from moving forward enough to

engage the full-auto position on the trigger nose, and by-pass the disconnector.

The selector levers themselves are the same except for deletion of the third

selector position notch. Very early semi-auto selectors were identical to the

SMG versions, and had all three control position notches already cut. Later

versions deleted the third position. Concurrent with the changes in the

semi-auto guns which resulted in their being redesignated as Model B, all

versions of UZI selector levers had a vertical safety tang added to the upper

surface of the lever, which prevented the sear from dropping (by blocking the

left underside sear finger, in the same mechanical fashion as the right

underside finger is blocked by the vertical tang of the grip safety) until the

selector switch was moved into one of the fire positions.

Now,

with the mode of fire changed, the fire controls had to be similarly altered.

All fire-control parts are contained in a separate housing attached centrally

below the receiver of the gun, and which also comprises the pistol grip and the

magazine well. The SMG fire-control assembly allows for three control positions,

safe, semi-auto, and full-auto. The selector levers have a small right angle,

finger-like, bent piece of metal which, in a SMG installation, moves forward and

bypasses the disconnector function in the fully forward full-auto position. For

semi-auto fire to occur it is placed in the middle position, where it can

function the disconnector, releasing the sear after the trigger nose drops. To

force the condition of semi-auto operation, whereby the disconnector is

activated continuously, it would be required to mechanically preclude the

selector from moving forward past this point. The alterations were made to the

semi-auto grip housing by adding a small block of metal inside the front center

shelf of this housing to preclude the selector from moving forward enough to

engage the full-auto position on the trigger nose, and by-pass the disconnector.

The selector levers themselves are the same except for deletion of the third

selector position notch. Very early semi-auto selectors were identical to the

SMG versions, and had all three control position notches already cut. Later

versions deleted the third position. Concurrent with the changes in the

semi-auto guns which resulted in their being redesignated as Model B, all

versions of UZI selector levers had a vertical safety tang added to the upper

surface of the lever, which prevented the sear from dropping (by blocking the

left underside sear finger, in the same mechanical fashion as the right

underside finger is blocked by the vertical tang of the grip safety) until the

selector switch was moved into one of the fire positions.

The

only other difference in the fire control parts relates to the sear itself. The

SMG sear is quite noticeably larger on the fingers that protrude up into the

receiver to catch the bolt. In comparison, the semi sear, because it only had to

restrain the much lighter striker mass, has smaller fingers. The smaller semi

sear will work but is NOT recommended, as excessive wear can result. A proper

conversion will have the sear projection holes in the bottom of the receiver

milled out to the correct dimensions to allow the factory SMG sear to be

installed and function. This was not always done, and on conversion guns

utilizing a registered bolt it may be looked upon as an illegal receiver

modification by BATF, unless the bolt was permanently married to the receiver by

serial number on the transfer form. (A note on all UZI sears; the sears, by

design, are made to a less hardened surface treatment than the bolt so that when

wear does occur, and it will, the comparatively cheaper sear can be replaced

rather than the entire expensive bolt. A highly worn sear can allow runaway

fire, in slips over the rounded, worn, sear fingers so always check the sear

condition on a regular basis!)

The

only other difference in the fire control parts relates to the sear itself. The

SMG sear is quite noticeably larger on the fingers that protrude up into the

receiver to catch the bolt. In comparison, the semi sear, because it only had to

restrain the much lighter striker mass, has smaller fingers. The smaller semi

sear will work but is NOT recommended, as excessive wear can result. A proper

conversion will have the sear projection holes in the bottom of the receiver

milled out to the correct dimensions to allow the factory SMG sear to be

installed and function. This was not always done, and on conversion guns

utilizing a registered bolt it may be looked upon as an illegal receiver

modification by BATF, unless the bolt was permanently married to the receiver by

serial number on the transfer form. (A note on all UZI sears; the sears, by

design, are made to a less hardened surface treatment than the bolt so that when

wear does occur, and it will, the comparatively cheaper sear can be replaced

rather than the entire expensive bolt. A highly worn sear can allow runaway

fire, in slips over the rounded, worn, sear fingers so always check the sear

condition on a regular basis!)

Lastly, on the fire control group, the axis pins that hold on the lower receiver control group onto the upper receiver have two different size mounting pins/holes, again to preclude a direct swapping of the SMG group onto the semi-auto receiver. The SMG uses a 8mm pins and receiver holes, while the semi-auto guns use 9mm pins and receiver holes. This prevents an SMG lower from being pinned on without enlarging the pinholes in the SMG trigger housing. You will still have to use 9mm pins to mount it. With the availability of parts kit guns now so abundant many people have chosen to install a real SMG lower, either for increased reliability, or just to get the Hebrew markings of the Israeli originals.

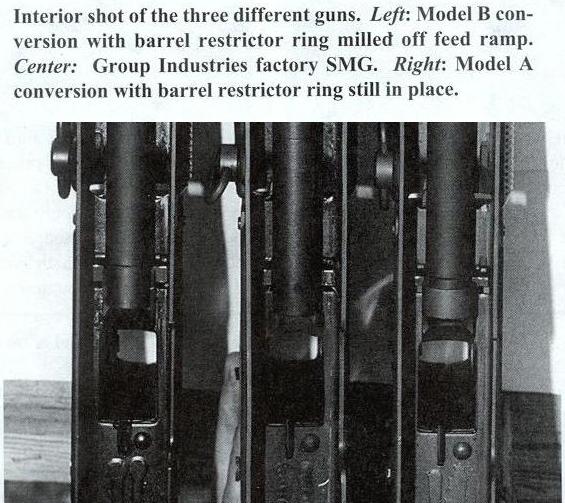

Jumping

back up into the front of the receiver, we discover yet another joyous

collection of maddening alterations that hinder our journey back to the world of

the original SMG configuration. The two most often heard complaints about owning

a conversion SMG relate to the barrel selection availability and mounting

problems. IMI thoughtfully left no stone unturned when redesigning the UZI for

semi-auto sale in the U.S. Their most fondly remembered alterations prevent the

installation and usage of cheap and plentiful SMG short barrels, instead forcing

the owner of an SMG conversion that has not been fully SMG configured to resort

to modifying and cutting down semi-auto barrels. Thankfully they are on the

after-market barrels that will interchange. (It should be noted that

possession of one of these short barrels that will drop into a semi-auto UZI and

the semi-auto UZI itself would comprise possession of a short barreled rifle,

requiring registration under Title II of the 1968 Gun Control Act.) The

semi-auto is different from the SMG as regards barrel mounting in two important

aspects. First, the actual barrel trunnion, which forms the heart of the forward

part of the upper receiver by being welded into place, has a smaller diameter

passage hole for the barrel flanges than on the SMG. This prevents an SMG barrel

from being slipped into the trunnion. On the front of the magazine well, inside

the bottom of the receiver, is welded on both SMG and semi-auto versions a

cartridge feed ramp to guide the nose of the bullet into the chamber of the

barrel. On the original SMG version that is all that it is, a cartridge guide.

On the semi-auto version it also contains a thick ring which serves to hold the

rear end of the barrel in position on the feed ramp, but more importantly it

prevents the larger rear diameter of a standard SMG barrel from being inserted

and utilized in the semi-auto conversion that does not have these two features

fixed. So one has to either cut and recrown the semi-auto barrels, or turn down

the flanges on the SMG versions. A proper and complete conversion will have had

the trunnion passage hole bored out to SMG spec, and the barrel ring milled off

the feed ramp.

Jumping

back up into the front of the receiver, we discover yet another joyous

collection of maddening alterations that hinder our journey back to the world of

the original SMG configuration. The two most often heard complaints about owning

a conversion SMG relate to the barrel selection availability and mounting

problems. IMI thoughtfully left no stone unturned when redesigning the UZI for

semi-auto sale in the U.S. Their most fondly remembered alterations prevent the

installation and usage of cheap and plentiful SMG short barrels, instead forcing

the owner of an SMG conversion that has not been fully SMG configured to resort

to modifying and cutting down semi-auto barrels. Thankfully they are on the

after-market barrels that will interchange. (It should be noted that

possession of one of these short barrels that will drop into a semi-auto UZI and

the semi-auto UZI itself would comprise possession of a short barreled rifle,

requiring registration under Title II of the 1968 Gun Control Act.) The

semi-auto is different from the SMG as regards barrel mounting in two important

aspects. First, the actual barrel trunnion, which forms the heart of the forward

part of the upper receiver by being welded into place, has a smaller diameter

passage hole for the barrel flanges than on the SMG. This prevents an SMG barrel

from being slipped into the trunnion. On the front of the magazine well, inside

the bottom of the receiver, is welded on both SMG and semi-auto versions a

cartridge feed ramp to guide the nose of the bullet into the chamber of the

barrel. On the original SMG version that is all that it is, a cartridge guide.

On the semi-auto version it also contains a thick ring which serves to hold the

rear end of the barrel in position on the feed ramp, but more importantly it

prevents the larger rear diameter of a standard SMG barrel from being inserted

and utilized in the semi-auto conversion that does not have these two features

fixed. So one has to either cut and recrown the semi-auto barrels, or turn down

the flanges on the SMG versions. A proper and complete conversion will have had

the trunnion passage hole bored out to SMG spec, and the barrel ring milled off

the feed ramp.

The last important difference between the SMG and the semi-auto carbine is in the design of the top covers. The SMG cover has an extra mechanism in the cocking track designed to prevent inadvertent discharge of the weapon if the cocking knob is accidentally released prior to full rearward travel being reached and sear lock-up of the bolt. This is commonly called a ratcheting top cover, due to the small ratchet mechanism which will catch and hold the bolt. This is only a feature in the open-bolt guns. It is not found, or needed, in a closed bolt firing weapon. The visible tip off to identification is the row of ratchet teeth along the side of the top cover bottom track. Semi-auto tracks are smooth for their entire length. There is also a slight difference in the length of the cut opening between the SMG and semi-auto carbine top cover tracks, which will be explained below. A proper conversion need not have this ratcheting top cover to function correctly, but anything designed, and available to the owner/operator, for safety reasons should be utilized. It is not possible to modify the semi-auto top cover for this ratcheting mechanism (for all practical purposes at least), so most complete conversions will have this entire assembly exchanged for a standard SMG unit. The other bonus benefit to this exchange of top covers is that the semi-auto carbine has a lengthy and annoying warning against illegal conversions stamped into the cocking knob slide, and since we're discussing a legal NFA registered weapon, it's only fitting to eliminate such aggravating visible verbiage on the exterior of the weapon. (See Photo on page 73.)

There is one more aesthetic difference between the semi-auto carbine and the SMG. Both guns could utilize either a folding metal stock or a fixed wooden one. The folders attach semi-permanently in the same fashion on either gun, but on the SMG the wooden stock is provisioned for quick detachment by a release lever on the stock underside. On the semi-auto carbine, the wooden stock is semi-permanently attached. The SMG quick-detach wooden stock will interchange for those who so desire.

Copyright © 2002-2017, UZITalk.com

International copyright laws

DO apply to

Internet Web Sites!

All Rights Reserved.

Last Modified: May 28, 2017

Contact:

librarian@uzitalk.com